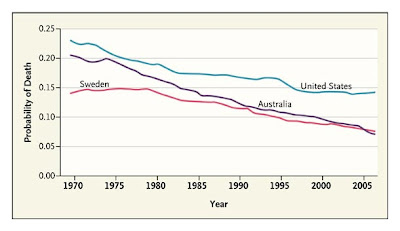

Probability of death in males 15-60 in US, Australia and Sweden; 1970-2005

(Compiled by US official data and World Health Organization)

By Sandy Prisant

In the week we apparently have decided to adopt collective amnesia and opt for total denial rather than health care reform, don't walk just yet. Remember that the problems won't be walking away. And remember that left unsolved, they will simply scuttle all the other economic stuff you'd now prefer to think about:

Ranking 37th —

Measuring the Performance of the U.S. Health Care System

Christopher J.L. Murray, M.D., D.Phil., and Julio Frenk, M.D., Ph.D., M.P.H.

New England Journal of Medicine (6/1/10)

Evidence that other countries perform better than the United States in ensuring the health of their populations is a sure prod to the reformist impulse. The World Health Report 2000, Health Systems: Improving Performance, ranked the U.S. health care system 37th in the world1 — a result that has been discussed frequently during the current debate on U.S. health care reform.

The conceptual framework underlying the rankings2 proposed that health systems should be assessed by comparing the extent to which investments in public health and medical care were contributing to critical social objectives: improving health, reducing health disparities, protecting households from impoverishment due to medical expenses, and providing responsive services that respect the dignity of patients. Despite the limitations of the available data, those who compiled the report undertook the task of applying this framework to a quantitative assessment of the performance of 191 national health care systems. These comparisons prompted extensive media coverage and political debate in many countries. In some, such as Mexico, they catalyzed the enactment of far-reaching reforms aimed at achieving universal health coverage. The comparative analysis of performance also triggered intense academic debate, which led to proposals for better performance assessment.

Despite the claim by many in the U.S. health policy community that international comparison is not useful because of the uniqueness of the United States, the rankings have figured prominently in many arenas. It is hard to ignore that in 2006, the United States was number 1 in terms of health care spending per capita but ranked 39th for infant mortality, 43rd for adult female mortality, 42nd for adult male mortality, and 36th for life expectancy.3 These facts have fueled a question now being discussed in academic circles, as well as by government and the public: Why do we spend so much to get so little? Comparisons also reveal that the United States is falling farther behind each year (see graph). In 1974, mortality among boys and men 15 to 60 years of age was nearly the same in Australia and the United States and was one third lower in Sweden. Every year since 1974, the rate of death decreased more in Australia than it did in the United States, and in 2006, Australia’s rate dipped lower than Sweden’s and was 40% lower than the U.S. rate. There are no published studies investigating the combination of policies and programs that might account for the marked progress in Australia. But the comparison makes clear that U.S. performance not only is poor at any given moment but also is improving much more slowly than that of other countries over time. These observations and the reflections they should trigger are made possible only by careful comparative quantification of various facets of health care systems.

Of course, international comparisons are not the only rankings that should inform the debate about reforming the health care system. Within the United States, there are dramatic variations among regions and racial or ethnic groups in the rates of death from preventable causes. While aiming to provide solutions to the problems of incomplete insurance coverage and inefficiency of care delivery, health care reformers have given insufficient attention to the design, funding, and evaluation of interventions that are tailored to local realities and address preventable causes of death. The big picture — the poor and declining performance of the United States, which goes far beyond the challenge of universal insurance — will inevitably get lost if we do not routinely track performance and compare the results both among countries and among states and counties within the United States.

Although many challenges remain, the available methods and data are better now than they were when the World Health Organization’s rankings were determined. As part of its reform efforts, the U.S. government should support and participate in international comparisons while commissioning regular performance assessments at the state and local levels.

Experience has shown that whenever a country embarks on large-scale reform of its health care system, periodic evaluations become a key instrument of stewardship to ensure that initial objectives are being met and that midcourse corrections can be made in a timely and effective manner. To be valid and useful, such evaluations cannot be an afterthought that is introduced once reform is under way. Instead, scientifically designed evaluations must be an integral part of the design of reform. For instance, the recent Mexican reform adopted from the outset an explicit evaluation framework that included a randomized trial to compare communities that were introducing insurance in the first phase of reform with matched communities that were scheduled to adopt the plan later. This external evaluation was coupled with internal monitoring meant to enable policymakers to learn from implementation.

In addition to its technical value, the explicit assessment of reform efforts contributes to transparency and accountability. Such assessments can also boost popular support for reform initiatives that inevitably stir up fears of the unknown. In the polarized political climate surrounding the current U.S. health care reform debate, the prospect of periodic evaluations may help reformers to counter many objections by offering a transparent and timely way of dealing with unintended effects. Built-in evaluations may be the missing ingredient that will allow us to finally reform health care in the United States.